|

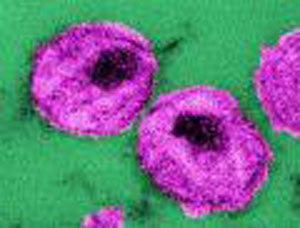

This thin-section transmission electron

micrograph (TEM) depicted the ultrastructural details of a

number of "human immunodeficiency virus" (HIV) virus

particles, or virions.

This thin-section transmission electron

micrograph (TEM) depicted the ultrastructural details of a

number of "human immunodeficiency virus" (HIV) virus

particles, or virions.

Photo courtesy of CDC; photo credit: Cynthia Goldsmith.

The National Healthcare Safety

Network (NHSN) is a secure, internet-based surveillance system

that integrates patient and healthcare personnel safety surveillance

systems managed by the Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion

(DHQP) at CDC. The NHSN was established in 2005 and integrates

three former networks: The National Nosocomial Surveillance

System (NNIS), the Dialysis Surveillance Network (DSN), and

the National Surveillance System for Healthcare Workers (NaSH).

Although most NHSN facilities voluntarily report data, some

states, including New York State, have mandatory reporting.

Facilities report their healthcare associated infection (HAI)

surveillance data for aggregation into a single national database

for the following purposes (CDC, 2008):

- Estimation of the magnitude of HAI;

- Discovery of HAI trends;

- Facilitation of inter-and intrahospital comparisons with

risk-adjusted data that can be used for local quality improvement

activities; and

- Assistance for facilities in developing surveillance and

analysis methods that permit timely recognition of patient

safety problems and prompt intervention with appropriate

measures.

Currently the majority of facilities in the NHSN system are

hospitals, however, the enrollment in this system is growing

to include other healthcare facilities such as long term care,

ambulatory surgery centers, and others (Edwards, et al., 2008).

As indicated previously, almost 2 million HAIs occur annually

and 99,000 people die from these infections (CDC, 2007). Of

those infections, 99,000 people die from these infections

(CDC, 2007). The frequency of healthcare associated infections

varies by body site. Of the 1.7 million infections reported

among patients, the most common healthcare-associated infections

are (CDC, 2007a):

- urinary tract infections (32 percent),

- surgical site infections (22 percent),

- pneumonias (15 percent), and

- bloodstream infections (14 percent).

According to the CDC (2006), the following are pathogens

and infectious diseases that can potentially be acquired in

healthcare settings (these illnesses are linked to the CDC

website in the event the learner would like more information

about each disease):

In 2009, the CDC published the Direct Medical Costs of

Healthcare-Associated Infections in US Hospitals and the Benefits

of Prevention. This report used results from published

medical and economic literature to provide a range of estimates

for the annual direct hospital cost of treating healthcare-associated

infections (HAIs) in the United States. Applying two different

Consumer Price Index (CPI) adjustments to account for the

rate of inflation in hospital resource prices, the overall

annual direct medical costs of HAI to U.S. hospitals ranges

from $28.4 to $33.8 billion (after adjusting to 2007 dollars).

Clearly the prevalence of HAIs contributes significantly

to increased morbidity, mortality and cost in healthcare.

Therefore, it is critical that healthcare professionals do

all they can to minimize the risk that their behavior contributes

to the spread of infection.

Healthcare professionals, although well aware of the importance

of accepted principles and practices of infection control,

may at times, for multiple reasons, fail to follow these accepted

principles and practices. However, professionals have both

an ethical and professional responsibility to adhere

to scientifically accepted or evidence based practices and

principles of infection control.

There are multiple organizations that have developed "best

practices" related to infection control. For example, the

CDC has developed multiple guidelines for preventing infections

in patients and healthcare personnel, as well as treatment

guidelines, should exposure occur. These guidelines can be

accessed from the CDC website at http://www.cdc.gov/hai/.

Other organizations that focus on scientifically accepted

practices and principles of infection control include:

Multiple professional disciplines' Codes of Ethics

require that the professional maintain current knowledge in

the field.

In 1999 New York State included the legal responsibility

to adhere to such principles. A law was passed in which the

professional may be charged with unprofessional conduct if

he or she fails to adhere to scientifically accepted principles

and practices of infection control. This is true for the professional

her or himself, but also true for those whom the professional

has clinical or administrative oversight. In 2008, physicians,

physician assistants and specialist assistants were added

to the professions who had a legal responsibility to adhere

to scientifically accepted principles and practices of infection

control and they now can be disciplined if they fail to do

so.

Some examples of these legal requirements may include:

- An attending physician does not correct the resident physician

in the emergency room who has neglected to utilize the "sharps"

containers after giving injections to patients;

- A licensed practical nurse does not intervene to correct

a certified nursing assistant who does not wash his/her

hands after providing care to a resident in a long term

care facility;

- Certified nursing assistant, for whom the registered

nurse has supervisory responsibility, does not wash her

hands after removing gloves after completing care to a resident

in a long term care facility. The nurse can be charged with

unprofessional conduct if she does not intervene to correct

the situation;

- An registered nurse witnesses a colleague utilizing unsafe

injection practices and does nothing;

- A laboratory supervisor who looks the other way with one

lab technician, an excellent employee, who just can't seem

to remember to wear gloves during phlebotomy;

- A dentist who witnesses the assistant not changing gloves

between patients and does not intervene.

- A registered nurse, in the operating room, notes that

the temperature and the humidity in the storage room is

unusually high and wonders if the sterilized instruments

used by the OR staff may be contaminated, but takes no action.

All of the examples above illustrate that professionals must

take the responsibility to adhere to scientific principles

of infection control. They must themselves practice in such

a manner, but in addition, New York State Law requires that

these professionals must also insure that those for whom they

have administrative or clinical oversight also practice to

this standard. Professionals who fail to follow accepted standards

of infection control will have the complaint investigated.

Possible outcomes of such charges include: disciplinary action,

revocation of professional license and professional liability.

Continue to

|

|