|

Hand Hygiene

The most common way that infection is spread throughout the

healthcare system is through hand contact. Indeed, handwashing

and hand hygiene are the single most effects means of limiting

the spread of infection. Despite the sophistication of healthcare

and the science behind that care, the simple and low-tech

intervention of hand hygiene is a significant factor in reducing

the spread of infection.

Handwashing should occur (CDC, 2002):

- Whenever hands are visibly dirty or contaminated.

- Before:

- having contact with patients

- putting on gloves

- inserting any invasive device

- manipulating an invasive device

- After:

- having contact with a patient's skin

- having contact with bodily fluids or excretions,

non-intact skin, wound dressings, contaminated items

- having contact with inanimate objects near a patient

- removing gloves

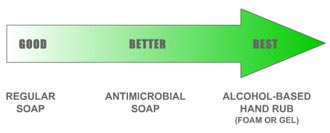

Alcohol-bashed hand rubs, either foam or gel, kill more effectively

and more quickly than handwashing with soap and water. They

are also less damaging to the skin, resulting in less dryness

and irritation, leading to fewer breaks in the skin. Hand

rubs require less time than handwashing with soap and water

and bottles/dispensers can be conveniently placed at the point

of care, to be more accessible (CDC, 2002).

ALCOHOL-BASED HAND

RUBS ARE MORE EFFECTIVE IN KILLING BACTERIA THAN SOAP AND

WATER

An alcohol-based hand rub is the preferred method

for hand hygiene in all situations, except for when your hands

are visibly dirty or contaminated.

HAND RUB (foam and gel)

- Apply to palm of one hand (the amount used depends on

specific hand rub product).

- Rub hands together, covering all surfaces, focusing in

particular on the fingertips and fingernails, until dry.

Use enough rub to require at least 15 seconds to dry.

HANDWASHING

- Wet hands with water.

- Apply soap.

- Rub hands together for at least 15 seconds, covering

all surfaces, focusing on fingertips and fingernails.

- Rinse under running water and dry with disposable towel.

- Use the towel to turn off the faucet.

Sharp instruments and disposable items must be properly

handled and disposed. Needles are NOT to be recapped,

purposely bent or broken, removed from disposable syringes

or otherwise manipulated by hand. After they are used, disposable

syringes and needles, scalpel blades and other sharp items

are to be placed in puncture-resistant, labeled containers

for sharps disposal. It is important that these containers

be conveniently located, as close as possible to where they

will be used. Additionally, it is important to not overfill

the sharps containers as placing items into these containers

poses risk when the container is overflowing with needles,

syringes and other sharp objects.

Housekeeping is important to maintain the work area

in a clean and sanitary condition. The employer is required

to determine and implement a written schedule for cleaning

and disinfection based on the location within the facility,

type of surface to be cleaned, type of soil present and tasks

or procedures being performed. All equipment, environmental

and working surfaces must be properly cleaned and disinfected

after contact with blood or OPIM.

Potentially contaminated broken glassware must be

removed using mechanical means, like a brush and dustpan or

vacuum cleaner. Specimens of blood or OPIM must be placed

in a closeable, labeled or color-coded leakproof container

prior to being stored or transported.

Chemical germicides and disinfectants used at recommended

dilutions must be used to decontaminate spills of blood and

other body fluids. Consult the Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA) lists of registered sterilants, tuberculocidal disinfectants,

and antimicrobials with HIV efficacy claims for verification

that the disinfectant used is appropriate. The lists are available

from the National Antimicrobial Information Network at (800)

858-7378 or http://npic.orst.edu/ptype/amicrob/pathogens.html.

Laundry that is or may be soiled with blood or OPIM,

and/or may contain contaminated sharps, must be treated as

though contaminated. Contaminated laundry must be bagged at

the location where it was used, and shall not be sorted or

rinsed in patient-care areas. It must be placed and transported

in bags that are labeled or color-coded (red-bagged).

Laundry workers must wear protective gloves and other appropriate

personal protective clothing when handling potentially contaminated

laundry. All contaminated laundry must be cleaned or laundered

so that any infectious agents are destroyed.

Waste disposal procedures must be carefully followed.

All infectious waste must be placed in closeable, leakproof

containers or bags that are color-coded (red-bagged) or labeled

as required to prevent leakage during handling, storage and

transport. Disposal of waste shall be in accordance with federal,

state and local regulations.

Tags or labels must be used as a means to prevent

accidental injury or illness to employees who are exposed

to hazardous or potentially hazardous conditions, equipment

or operations which are out of the ordinary, unexpected or

not readily apparent. Tags must be used until the identified

hazard is eliminated or the hazardous operation is completed.

Personal activities such as eating, drinking,

smoking, applying cosmetics or lip balm, and handling contact

lenses are prohibited in laboratories and other work areas

where blood or OPIM are present.

Food and drink must not be stored in refrigerators,

freezers or cabinets where blood or OPIM are stored, or in

other areas of possible contamination.

Bloodborne Pathogen Training

All new employees or employees being transferred into jobs

involving tasks or activities with potential exposure to blood/OPIM

shall receive training in the Bloodborne Pathogen Standard

at the time of initial assignment to the tasks where occupational

exposure may occur. This training will include information

on the hazards associated with blood/OPIM, the protective

measures to be taken to minimize the risk of occupational

exposure, and information on the appropriate actions to take

if an exposure occurs.

Retraining is required annually, or when changes in procedures

or tasks affecting occupational exposure occur. As previously

mentioned, the limited information in this section does not

qualify for the full training.

All employees whose jobs involve participation in tasks or

activities with exposure to blood/OPIM shall be offered the

start of the Hepatitis B vaccination series within

10 working days of employment and/or new assignment. The vaccine

will be provided free of charge. Serologic testing after vaccination

(to ensure that the shots were effective) is recommended for

all persons with occupational exposures.

Risk of Occupational exposures

The CDC states that the risk of infection for HIV, HBV or

HCV in the healthcare setting varies from case by case. Factors

influencing the risk of infection from occupational exposure

are:

- Whether the exposure was from a hollow-bore needle or

other sharp instrument;

- To intact skin or mucus membranes (such as the eyes,

nose, mouth);

- The amount of blood that was involved and

- The amount of virus present in the source's blood

The risk of HIV infection to a healthcare worker through

a needlestick is less than 1%. Approximately 1 in 300 exposures

through a needle or sharp instrument result in infection.

The risks of HIV infection through splashes of blood to the

eyes, nose or mouth is even smaller - approximately 1 in 1,000.

There have been no reports of HIV transmission from blood

contact with intact skin. There is a theoretical risk of blood

contact to an area of skin that is damaged, or from a large

area of skin covered in blood for a long period of time. In

2001, the CDC reported 56 documented cases and 138 possible

cases of occupational exposure to HIV since reporting started

in 1985. The risk of getting HBV from a needlestick or cut

is between 6-30%, unless the person exposed has been vaccinated

to hepatitis B. There are only a few studies regarding the

risk of getting HCV from occupational exposure. The risk of

getting HCV from a needlestick or cut is between 2-3%. The

risk of getting HBV or HCV from a blood splash to the eyes,

nose or mouth is possible but believed to be very small. As

of 1999, about 800 health care workers a year are reported

to be infected with HBV following occupational exposure. There

are no exact estimates on how many healthcare workers contract

HCV from an occupational exposure. To put this in perspective,

the risk of a healthcare worker contracting HCV from an accidental

needlestick is 20-40% greater than their risk of contracting

HIV.

Treatment After a Potential Occupational

Exposure

It is important to follow the protocol of your employer.

The CDC recommends that post-exposure prophylaxis should be

started ideally within 2 hours of occupational exposure (CDC,2005).

The CDC recommends that as soon as safely possible, wash the

affected area(s). Application of antiseptics should not be

a substitute for washing. It is recommended that any potentially

contaminated clothing be removed as soon as possible. It is

also recommended that you familiarize yourself with existing

protocols and the location of emergency eyewash or showers

and other stations within your facility.

If the HIV exposure is to the eyes, nose or mouth, flush

them continuously with water, saline or sterile irrigants

for at least five minutes. The risk of contracting HIV through

this type of exposure is estimated to be 0.09%.

In the event of a needlestick injury, wash the exposed area

with soap and clean water. Do not "milk" or squeeze the wound.

There is no evidence that shows using antiseptics (like hydrogen

peroxide) will reduce the risk of transmission for any bloodborne

pathogens. In the event that the wound needs suturing, emergency

treatment should be obtained. The risk of contracting HIV

from this type of exposure is estimated to be 0.3%.

Exposure to saliva is not considered substantial unless

there is visible contamination with blood. Wash the area with

soap and water, and cover with a sterile dressing as appropriate.

All bites should be evaluated by a healthcare professional.

Exposure to urine, feces, vomit or sputum is not considered

substantial unless the fluid is visibly contaminated with

blood. Follow normal procedures for cleaning these fluids.

Reporting the Exposure

Follow the protocol of your employer. The following general

guidelines taken from the CDC are not meant to replace an

existing protocol. After cleaning the exposed area as recommended

above, report the exposure to the department or individual

at your workplace that is responsible for managing exposure.

Obtain medical evaluation as soon as possible. Discuss with

a healthcare professional the extent of the exposure, prophylaxis/prevention

of other bloodborne pathogens, the need for a tetanus shot

and other care.

Post-exposure Prophylaxis

Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) provides anti-HIV medications

to someone who has had a substantial exposure, usually to

blood. PEP has been the standard of care for occupationally-exposed

healthcare workers with substantial exposures since 1996.

Animal models suggest that cellular HIV infection happens

within 2 days of exposure to HIV. Virus in blood is detectable

within 5 days. Therefore, PEP should be started as soon as

possible, optimally within 2 hours, preferably within 24

hours of the exposure or as soon as possible and continued

for 28 days. However, PEP for HIV does not provide prevention

of other bloodborne diseases, like HBV or HCV.

HBV PEP for susceptible persons would include administration

of hepatitis B immune globulin and HBV vaccine. This should

occur as soon as possible and no later than 7 days post-exposure.

There are currently no recommendations for HCV exposure.

There have been several changes in CDC (2005) recommendations

for post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP). These changes are based

on new scientific evidence that resulted from research focused

on viral transmission following occupational and non-occupational

exposures. The most current recommendations can be found at

the CDC website and are available in downloadable format for

use in emergency departments and medical offices.

The CDC (2005) currently recommends PEP for occupational

exposures:

PEP should be initiated as soon as possible, preferably

within hours rather than days of exposure. If a question

exists concerning which antiretroviral drugs to use, or

whether to use a basic or expanded regimen, the basic regimen

should be started immediately rather than delay PEP administration.

The optimal duration of PEP is unknown. Because 4 weeks

of zidovudine appeared protective in occupational and animal

studies, PEP should be administered for 4 weeks, if tolerated.

Combinations that can be considered for PEP include ZDV

and 3TC or emtricitabine (FTC); d4T and 3TC or FTC; and

tenofovir (TDF) and 3TC or FTC. In the previous Public Health

Service guidelines, a combination of d4T and ddI was considered

one of the first-choice PEP regimens; however, this regimen

is no longer recommended because of concerns about toxicity

(especially neuropathy and pancreatitis) and the availability

of more tolerable alternative regimens.

The PI preferred for use in expanded PEP regimens is lopinavir/ritonavir

(LPV/RTV). Other PIs acceptable for use in expanded PEP

regimens include atazanavir, fosamprenavir, ritonavir-boosted

indinavir, ritonavir-boosted saquinavir, or nelfinavir.

Although side effects are common with Non-nucleoside Reverse

Transcriptase inhibitors, efavirenz may be considered for

expanded PEP regimens, especially when resistance to PIs

in the source person's virus is known or suspected. Caution

is advised when EFV is used in women of childbearing age

because of the risk of teratogenicity (CDC, 2005).

For non-occupational exposures (nPEP), the recommendations

are as follows:

For persons seeking care <72 hours after non-occupational

exposure to blood, genital secretions, or other potentially

infectious body fluids of a person known to be HIV infected,

when that exposure represents a substantial risk for transmission,

a 28-day course of highly active antiretroviral therapy

(HAART) is recommended. Antiretroviral medications should

be initiated as soon as possible after exposure. For persons

seeking care <72 hours after non-occupational exposure to

blood, genital secretions, or other potentially infectious

body fluids of a person of unknown HIV status, when such

exposure would represent a substantial risk for transmission

if the source were HIV infected, no recommendations are

made for the use of nPEP. Clinicians should evaluate risks

and benefits of nPEP on a case-by-case basis. For persons

with exposure histories that represent no substantial risk

for HIV transmission or who seek care >72 hours after exposure,

DHHS does not recommend the use of nPEP (CDC, 2005a).

Post-exposure prophylaxis can only be obtained from a licensed

healthcare provider. Your facility may have recommendations

and a chain of command in place for you to obtain PEP. After

evaluation of the exposure route and other risk factors, certain

anti-HIV medications may be prescribed.

The specific details about post-exposure management and treatment

see the CDC (2005) Updated US Public Health Guidelines for

the management of occupational exposures to HIV and recommendations

for postexposure prophylaxis. MMWR, 54(RR09), 1-17, available

at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5409a1.htm.

PEP is not as simple as swallowing one pill. The medications

must be started within the first 2 hours if possible, and

continued for 28 days. Many people experience significant

medication side effects.

It is very important to report occupational exposure to

the department at your workplace that is responsible for managing

exposure. If post-exposure treatment is recommended, it should

be started as soon as possible.

In rural areas, police, firefighters and other at-risk emergency

providers should identify a 24-hour source for PEP. The national

bloodborne pathogen hotline provides 24-hour consultation

for clinicians who have been exposed on the job. Call 1-888-448-4911

for the latest information on prophylaxis for HIV, hepatitis,

and other pathogens.

HIV/HBV/HCV Testing Post-exposure

As a healthcare professional, if one sustains an occupational

exposure to HIV, HBV and HCV, antibody testing for HIV, HBV

and HCV, as well as vaccination for HBV will be offered. Since

it usually takes the body between two weeks and three months

to produce antibodies to HIV, the initial test serves as a

baseline. It will show whether HIV infection occurred prior

to this exposure. Additional testing will be needed. In 2001,

the CDC recommended retesting at six weeks, 3 and 6 months

after exposure. Testing for up to 12 months may be recommended

for high risk exposures or when the source is documented to

be infected with HIV. The need for a Hepatitis B titer test

(if previously vaccinated for HBV), tests for elevated liver

enzymes and other available testing for other bloodborne pathogens

should be discussed with the healthcare provider.

There are situations where healthcare workers and others

are not aware of the HIV status of the individual to whose

blood they have been exposed. Usually, you can't force someone

to test for HIV and reveal their results to you.

If an occupational exposure occurs, the exposed person can

request HIV testing of the source individual. However, the

source must consent to the testing. Source testing does not

eliminate the need for baseline testing of the exposed individual

for HIV, HBV, HCV and liver enzymes. Provision of PEP should

also not be contingent upon the results of a source's test.

Current wisdom indicates immediate provision of PEP, with

discontinuation of treatment based upon the source's test

results.

The risk of HIV infection to a healthcare worker from a needlestick

containing HIV-positive blood is about 1 in 300, according

to CDC data. Risks for infection with found syringes will

depend on a variety of factors, including the amount of time

the syringe was left out, presence of blood and the type of

injury (scratch versus puncture).

Continue on to Legal

Aspects of HIV/AIDS: Testing, Counseling and Confidentiality

|