|

Although HIV infection affects people from all ethnic groups,

genders, ages, and income levels, some groups have been significantly

affected by the AIDS epidemic. These groups have included

men who have sex with men, injecting drug users, people with

hemophilia, women, and people of color. The difference with

the grief process associated with HIV and AIDS can be the

social and emotional issues associated with contracting the

disease. The following information details how these different

populations may be uniquely affected by the AIDS epidemic.

Men Who Have Sex With Men

Despite gains in human rights, our American society still

has issues with men who have sex with men. Grief may not be

validated when relationships are considered "unacceptable."

An example of this may be the reaction of churches to those

who are living with, or have families living with AIDS. Many

congregants report that they do not get the support they need

from their church families because of the stigma attached

to HIV, AIDS and to men who have sex with men.

Self-esteem issues and psychological issues (including depression,

anxiety, diagnosed mental illness and risk-taking behaviors)

may also complicate the lives of these men. Additionally,

there are the issues with HIV-negative men who have sex with

men. Most of the attention, resources and services are focused

on HIV-positive men. As with any behavior change people can

become "tired" with safer sex messages, and may make choices

that place them at risk. Some may feel that HIV infection

is inevitable (although it is not) and purposely engage in

unprotected sex.

Injecting Drug Users

American society also has issues with illegal drug use and

the way we view marginalized individuals such as those in

poverty and the homeless. Drug users are also stigmatized.

People who continue to use injecting drugs, despite warnings

and information about risks, may be viewed by some as "deserving"

their infection. However, it is important to remember that

addiction is an illness and rarely does "just say no" work

to stop the addiction; indeed it trivializes the seriousness

of addiction.

Harm reduction measures like syringe exchange programs, have

been proven to reduce the transmission of blood-borne pathogens

like HIV, HBV, and HCV. These programs are controversial because

some people believe that providing clean needles and a place

to exchange used needles constitutes "approval" of injection

drug use.

In addition to poverty, self-esteem issues and psychological

issues, including depression, anxiety, diagnosed mental illness

and risk-taking behaviors, may also complicate the lives of

injection drug users. The desire to stop using illegal drugs

and the ability to do so may be very far apart. The reality

about inpatient treatment facilities is there are very few

spaces available for the demand. Many injecting drug users

are placed on "waiting lists" when they want treatment, and

by the time there is a place for them, the individual may

be lost to follow-up.

People with Hemophilia

Hemophiliacs lack the ability to produce certain blood clotting

factors. Before the advent of antihemophilic factor concentrates

(products like "factor VIII" and "factor IX," which are clotting

material pooled out of donated blood plasma), hemophiliacs

could bleed to death. These concentrates allowed hemophiliacs

to receive injections of the clotting factors that they lacked,

which in turn allowed them to lead relatively normal lives.

Unfortunately, because the raw materials for these concentrates

came from donated blood, many hemophiliacs were infected with

HIV prior to the advent of blood testing.

During the 1980's, prior to routine testing of the blood

supply, 90% of severe hemophiliacs contracted HIV and/or HCV

through use of these products. There is anger within this

community because there is evidence to show that the companies

manufacturing the concentrates knew their products might be

contaminated, but continued to distribute them anyway.

While some people considered hemophiliacs to be "innocent

victims" of HIV, there had been significant discrimination

against them. The Ryan White Care Act, funding HIV services,

and the Ricky Ray Act, which provides compensation to hemophiliacs

infected with HIV, were both named after HIV-positive hemophiliacs

who suffered significant discrimination (arson, refusal of

admittance to grade school, etc.) in their hometowns.

Women

Certain strains of HIV may infect women more easily. The

strain of HIV present in Thailand seems to transmit more easily

to women through sexual intercourse.

Researchers believe that women and receptive partners are

more easily infected with HIV, compared to the insertive partner.

Receptive partners are at greater risk for transmission of

any sexually transmitted disease, including HIV.

Women infected with HIV are at increased risk for a number

of gynecological problems, including pelvic inflammatory disease,

abscesses of the fallopian tubes and ovaries, and recurrent

yeast infections. Some studies have found that HIV-infected

women have a higher prevalence of infection with the human

papilloma virus (HPV). Cervical dysplasia is a precancerous

condition of the cervix cause by certain strains of HPV. Cervical

dysplasia in HIV-infected women often becomes more aggressive

as the woman's immune system declines. This may lead to invasive

cervical carcinoma, which is an AIDS-indicator condition.

It is important for women with HIV to have more frequent Pap

tests.

Several studies have shown that women with HIV in the U.S.

receive less health care services and HIV medications, compared

to men. This may be because women aren't diagnosed or tested

as frequently as men.

The number of women with HIV (human immunodeficiency virus)

infection and AIDS has been increasing steadily worldwide.

By the end of 2003, according to the World Health Organization

(WHO), 19.2 million women were living with HIV/AIDS worldwide,

accounting for approximately 50 percent of the 40 million

adults living with HIV/AIDS (NIAID, 2004).

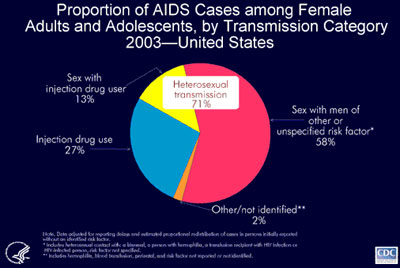

Figure 1. Proportion of AIDS Cases among

Female Adults and Adolescents, by Transmission Category 2003-United

States (CDC, 2005e).

CDC estimates that 71% of the 11,498 AIDS cases

diagnosed among female adults and adolescents in 2003 can

be attributed to heterosexual transmission: 13% of these cases

are from heterosexual contact with an injection drug user

and 58% from sexual contact with high-risk partners such as

bisexual men or HIV-infected men with unidentified risk factors

(CDC, 2005e). Of the cases in female adults and adolescents,

27% were attributed to injection drug use and 2% to other

or unidentified risk factors (CDC, 2005e).

Worldwide, more than 90 percent of all adolescent

and adult HIV infections have resulted from heterosexual intercourse.

Women are particularly vulnerable to heterosexual transmission

of HIV due to substantial mucosal exposure to seminal fluids.

This biological fact amplifies the risk of HIV transmission

when coupled with the high prevalence of non-consensual sex,

sex without condom use due to some women's inability to negotiate

safer sex practices with their partners, and the unknown and/or

high-risk behaviors of their partners (NIAID, 2004).

Younger women are also increasingly being diagnosed

with HIV infection, particularly among African-Americans and

Hispanics. Through December 2002, women aged 25 and younger

accounted for 9.8 percent of the female AIDS cases reported

to CDC (NIAID, 2004).

HIV disproportionately affects African-American

and Hispanic women. Together they represent less than 25 percent

of all U.S. women, yet they account for more than 82 percent

of AIDS cases in women (NIAID, 2004).

Women suffer from the same complications of

AIDS that afflict men but also suffer gender-specific manifestations

of HIV disease, such as recurrent vaginal yeast infections

and severe pelvic inflammatory disease, which increase their

risk of cervical cancer. Women also exhibit different characteristics

from men for many of the same complications of antiretroviral

therapy, such as metabolic abnormalities (NIAID, 2004).

Frequently, women with HIV infection have great

difficulty accessing healthcare; they may postpone taking

medication, or going to their own medical appointments because

of the heavy burden of caring for children and other family

members who may also be HIV-infected. They often lack social

support and face other challenges that may interfere with

their ability to adhere to treatment regimens (NIAID, 2004).

Women (and also men) may fear disclosing their HIV status

to others, out of fear of losing their jobs, housing, or other

forms of discrimination. Single parents with HIV may feel

particularly fearful because of their lack of support.

Many women have problems with lack of transportation,

lack of health insurance, limited education and low income.

They may have child-care problems that prevent them from going

to medical appointments.

Many women who have HIV infection do not consider

this to be their "worst problem". Their symptoms may be mild

and manageable for many years. Meanwhile, they may have more

pressing concerns, such as their income, housing, access to

medical care, possible abusive relationships, and concerns

about their children.

Continue on to Select Populations

and HIV/AIDS, Con't.

|