|

People of Color

African Americans and Hispanics specifically

have disproportionately higher rates of AIDS cases in the

U.S., despite the fact that there are no biological reasons

for the disparities.

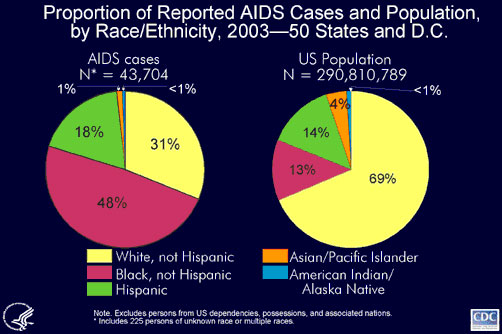

Figure 2. below illustrates the distribution

of AIDS cases reported in 2003 among racial/ethnic groups.

The pie chart on the right shows the distribution of the US

population (excluding US dependencies, possessions and associated

nations) in 2003.

Non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics are disproportionately

affected by the AIDS epidemic in comparison with their proportional

distribution in the general population. In 2003, non-Hispanic

blacks made up 13% of the population but accounted for 48%

of reported AIDS cases. Hispanics made up 14% of the population

but accounted for 18% of reported AIDS cases.

Non-Hispanic whites made up 69% of the US population

but accounted for 31% of reported AIDS cases.

Figure 2. Proportion of Reported AIDS Cases

and Population, by Race/Ethnicity, 2003-50 States and D.C.

(CDC, 2005b).

There is not one single reason that stands out

as to why the disparities exist. Multiple factors contribute

to racial/ethnic health disparities, including socioeconomic

factors (e.g., education, employment, and income), lifestyle

behaviors (e.g., physical activity and alcohol intake), social

environment (e.g., educational and economic opportunities,

racial/ethnic discrimination, and neighborhood and work conditions),

and access to preventive health-care services (e.g., cancer

screening and vaccination) (CDC, 2005c). Both legacies of

the past and current issues of race mean that many people

of Color do not trust "the system" for a variety of reasons.

Thus, even when income is not a barrier, access to early intervention

and treatment may be limited. And HIV may be only one of a

list of problems, which also include adequate housing, food,

employment, etc.

Photograph by Lloyd Wolf for the U.S. Census

Bureau, Public Information Office

Recent immigrants also can be at increased risk

for chronic disease and injury, particularly those who lack

fluency in English and familiarity with the U.S. healthcare

system or who have different cultural attitudes about the

use of traditional versus conventional medicine. Approximately

6% of persons who identified themselves as Black or African

American in the 2000 census were foreign-born (CDC, 2005c).

Photo by the U.S. Census Bureau, Public Information

Office

For African Americans in the US, health disparities

can mean earlier deaths, decreased quality of life, loss of

economic opportunities, and perceptions of injustice. For

society, these disparities translate into less than optimal

productivity, higher health-care costs, and social inequity.

By 2050, an estimated 61 million African American persons

will reside in the US, amounting to approximately 15% of the

total US population (CDC, 2005c).

Another factor may be the diversities within

these populations. Diversity is evident in immigrant status,

religion, languages, geographic locations and, again, socioeconomic

conditions. Getting information out in appropriate ways to

these diverse populations has been difficult.

There is a significant amount of denial about

HIV risk, which continues to exist in these communities. As

with other groups, there may also be fear and stigmatization

of those who have HIV. Prevention messages need to be tailored

in ways that are culturally appropriate and relevant. The

messages must be carried through channels that are appropriate

for the individual community. These channels may include religious

institutions or through respected "elders" in the community.

Ironically, it may be these institutions or elders who, in

the past, have contributed to the misinformation and stigma

associated with HIV. Many HIV prevention programs are recognizing

the need to work within these diverse communities to let the

communities lead the way in prevention the transmission of

HIV.

Adolescents/Young Adults

The effects of HIV and AIDS among adolescents

and young adults (ages 13 to 24) in the United States continues

to be an increasing concern. The CDC reported 38,490 cumulative

cases of AIDS among people ages 13 to 24 through 2003. Since

the epidemic began, an estimated 10,041 adolescents and young

adults with AIDS have died and the proportion diagnosed with

AIDS is increasing. Also, the proportion with an AIDS diagnosis

among adolescents and young adults has increased from 3.9

percent in 1999 to 4.7 percent in 2003 (NIAID, 2005).

Moreover, African-American and Hispanic adolescents

have been disproportionately affected by the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

Between the ages of 13 and 19, African-Americans and Hispanics

accounted for 66 percent and 21 percent, respectively, of

the reported AIDS cases in 2003 (NIAID, 2005).

Because the average duration from HIV infection

to the development of AIDS is 10 years, most adults with AIDS

were likely infected as adolescents or young adults. In 2003,

an estimated 3,897 were diagnosed with HIV/AIDS, while an

estimated 13,752 were living with HIV/AIDS. Health experts

estimate the number of adolescents and adults living with

HIV infection, however, to be much higher (NIAID, 2005).

Most HIV-infected adolescents and young adults

are exposed to the virus through sexual intercourse. Recent

HIV surveillance data suggest that the majority of HIV-infected

adolescent and young adult males are infected through sex

with men. Only a small percentage of males appear to be exposed

by injection drug use and/or heterosexual contact. The same

data also suggest that adolescent and young adult females

infected with HIV were exposed through heterosexual contact,

with a very small percentage through injection drug use. In

addition, there is an increasing number of children who were

infected as infants that are now surviving to adolescence

(NIAID, 2005).

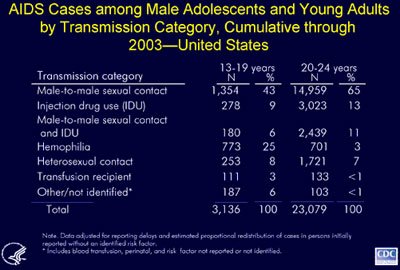

Table 1. AIDS Cases among Male Adolescents

and Young Adults by Transmission Category, Cumulative through

2003-United States (CDC, 2005d).

Nationally, since the beginning of the epidemic,

more than 3,100 adolescent males aged 13 to 19 years and approximately

23,000 young adult males aged 20 to 24 years have been reported

with AIDS (CDC, 2005d).

The majority (65%) of males aged 20 to 24 with

AIDS had a risk factor of male-to-male sexual contact and

an additional 11% were among males who reported risk factors

of male-to-male sexual contact and injection drug use (CDC,

2005d).

Approximately 25% of AIDS cases among adolescent

males aged 13-19 were among those who had hemophilia and acquired

their infection before blood products were heat treated to

prevent HIV transmission. In contrast, 3% of AIDS cases among

males aged 20-24 were attributed to receipt of blood products

for hemophilia (CDC, 2005d).

Injection drug use is more common among the

20 to 24 year old males reported with AIDS than among adolescents

with AIDS, but less common than among males over 24 years.

Eight percent of AIDS cases among males aged 13 to 19 and

7% of cases among males aged 20-24 years were reported with

heterosexual contact as their transmission category (CDC,

2005d).

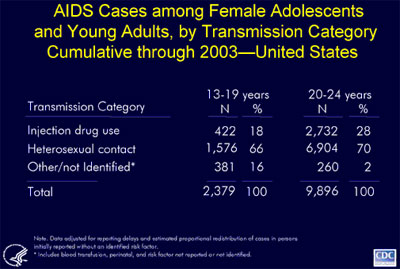

Table 2. AIDS Cases among Female Adolescents

and Young Adults, by Transmission Category Cumulative through

2003-United States (CDC, 2005d).

Approximately two-thirds of AIDS cases among

adolescent and young adult females were attributed to heterosexual

contact as the mode of exposure to HIV. Cases among adolescent

females were less likely to be attributed to injection drug

use than were cases among young adults (18% vs. 28% of cases)

(CDC, 2005d).

Photograph by Lloyd Wolf for the U.S. Census

Bureau, Public Information Office

Photograph by Heather Schmaedeke for U.S. Census

Bureau, Public Information Office

Approximately 25 percent of cases of sexually

transmitted infections (STIs) reported in the United States

each year are among teenagers. This is particularly significant

because the risk of HIV transmission increases substantially

if either partner is infected with an STI. Discharge of pus

and mucus as a result of STIs such as gonorrhea or chlamydia

infection also increase the risk of HIV transmission three-

to five-fold. Likewise, STI-induced ulcers from syphilis or

genital herpes increase the risk of HIV transmission nine-fold

(NIAID, 2005).

Adolescents and young adults tend to think they

are invincible and, therefore, deny any risks. This belief

may cause them to engage in risky behavior, delay HIV testing,

and if they test positive, delay or refuse treatment. The

inability to link them to medical care can lead to increased

transmission of HIV. Healthcare providers report that many

young people, when they learn they are HIV-positive, take

several months to accept their diagnosis and return for treatment

(NIAID, 2005).

Healthcare providers may be able to help young

people understand their situation during visits by (NIAID,

2005):

- Ensuring confidentiality.

- Explaining the information clearly.

- Eliciting questions.

- Emphasizing the success of newly available treatments.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) has

developed documents that address the standard of care for

the treatment of HIV, including information about how to treat

HIV in adolescents. The documents Guidelines for the Use

of Antiretroviral Agents in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents

and Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Pediatric

HIV Infection are available from AIDSinfo.

According to the Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral

Agents in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents, adolescents

exposed to HIV sexually or via injection drug use appear to

follow a clinical course that is more similar to HIV disease

in adults than in children. Most adolescents with sexually

acquired HIV are in a relatively early stage of infection

and are ideal candidates for early intervention that includes

education and counseling, identifying high-risk behaviors,

and recommended therapies and behavioral changes (NIAID, 2005).

Adolescents who were infected at birth or via blood products

as young children, however, follow a unique clinical course

that may differ from that of other adolescents and adults.

Healthcare providers should refer to the treatment guidelines

for detailed information about treating HIV-infected adolescents

(NIAID, 2005).

Children

Children show significant differences in their HIV disease

progression and their virologic and immunologic responses,

compared to adults. Without drug treatment, children may have

developmental delay, pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, failure

to thrive, recurrent bacterial infections and other conditions

related to HIV.

Photograph by Lloyd Wolf for the U.S. Census

Bureau, Public Information Office

The antiretroviral treatments that are available

for HIV infection may not be available in pediatric formulations.

The medications may have different side effects in children

than they do in adults.

It is vital that women know their HIV status

before or during pregnancy. Antiretroviral treatment significantly

reduces the chance that their child will become infected with

HIV. Prior to the development of antiretroviral therapies,

most HIV-infected children were very sick by seven years of

age. In 1994, scientists discovered that a short treatment

course of the medication AZT for pregnant women dramatically

reduced the number, and rate, of children who became infected

perinatally. C-sections for delivery in certain cases may

be warranted to reduce HIV transmission. As a result, perinatal

HIV infections have substantially declined in the developed

world.

Early diagnosis of HIV infection in newborns

is now possible. Antiretroviral therapy for infants is now

the standard of care, and should be started as soon as the

child is determined by testing to be HIV-infected. Current

recommendations are to treat apparently uninfected children

who are born to mothers who are HIV-positive with antiretroviral

medicines for six weeks, to reduce any possibility of HIV

transmission.

Persons Aged 50 and

Older

A growing number of older people now have HIV/AIDS.

About 19 percent of all people with HIV/AIDS in this country

are age 50 and older. Numbers of cases are expected to increase,

as people of all ages survive longer due to triple-combination

drug therapy and other treatment advances (NIA, 2005; NAHOF,

nd).

|

|

|

|

|

Courtesy of Administration

on Aging

|

But there may even be many more cases than we

know about. Why? One reason may be that healthcare providers

do not always test older people for HIV/AIDS and so may miss

some cases during routine check-ups. Another may be that older

people often mistake signs of HIV/AIDS for the aches and pains

of normal aging, so they are less likely than younger people

to get tested for the disease. Also, they may be ashamed or

afraid of being tested. People age 50 and older may have the

virus for years before being tested. By the time they are

diagnosed with HIV/AIDS, the virus may be in the late stages

(NIA, 2005).

Older people with HIV/AIDS face a double stigma:

ageism and infection with a sexually-or-IV-drug transmitted

disease (NAHOF, nd). The number of HIV/AIDS cases among older

people is growing every year because (NIA, 2005):

- Older Americans know less about HIV/AIDS than younger

people.

- They do not always know how it spreads or the importance

of using condoms, not sharing needles, getting tested for

HIV, and talking about it with their doctor or other healthcare

provider.

- Healthcare workers and educators often do not talk with

middle-age and older people about HIV/AIDS prevention.

- Older people are less likely than younger people to talk

about their sex lives or drug use with their doctors or

other healthcare providers.

- Doctors and other healthcare providers may not ask older

patients about their sex lives or drug use, or talk to them

about risky behaviors.

The number of cases of HIV/AIDS for older women

has particularly been growing over the past few years. The

rise in the number of cases in women of color age 50 and older

has been especially steep. Most got the virus from sex with

infected partners. Many others got HIV through shared needles

(NIA, 2005).

Because women may live longer than men, and

because of the high divorce rate, many widowed, divorced,

and separated women are dating these days. Like older men,

many older women may be at risk because they do not know how

HIV/AIDS is spread. Women who no longer worry about getting

pregnant may be less likely to use a condom and to practice

safe sex. Also, vaginal dryness and thinning often occurs

as women age; when that happens, sexual activity can lead

to small cuts and tears that raise the risk for HIV/AIDS (NIA,

2005).

Advice for Victims

of Sexual Assault

There are likely to be between 172,400 - 683,000

females raped each year in the U.S. Men can also be victims

of sexual assault, but data and reporting are limited. Based

on existing crime report data, an estimated 40% of female

rape victims are under age 18; most sexual assault victims

know their assailant. Apart from the emotional and physical

trauma that accompanies sexual assault, there are other considerations.

Many victims do not report their attack to the police.

According to CDC, the odds of HIV infection

from a sexual assault in the U.S. are 2 in 1,000. There are

additional risks for contracting other STDs, and females can

become pregnant. Emergency contraception is part of the medical

treatment for female rape victims. The emergency contraception

hotline number, 1-888-668-2528, should be provided by telephone

rape counselors or other counselors.

Most experts recommend that a sexual assault

victim go directly to the nearest hospital emergency room,

without changing their clothing, bathing or showering first.

Trained staff in the emergency room will counsel the victim,

and may also offer testing or referral for HIV, STDs and pregnancy.

It is common practice for the emergency room physician to

take DNA samples of blood or semen from the vagina, rectum,

etc. which can be used as evidence against the attacker. Some

emergency departments may refer sexual assault survivors to

the local health jurisdiction for HIV testing.

Many people feel that the emergency room setting

is a profoundly unpleasant time to question a sexual assault

victim regarding her/his sexual risks, etc. However, testing

shortly after a sexual assault will provide baseline information

on her/his status for the various infections. This information

can be useful for the victim and healthcare provider, especially

for follow-up care and treatment. Additionally, baseline information

can be used for legal and criminal action against the assailant.

Continue on to Management

of HIV in the Healthcare Workplace

|